In which we discuss the unexpected technical challenges of creating a movie poster.

The idea for the 10 Years of LCLS movie poster came out of discussion with LCLS management. They were looking for novel designs for a shirt or other similar corporate wear that could be part of the celebration for delivering 10 years of science at the facility. They contacted me for some help coming up with ideas and advising on the production. I took some of the material they’d put together, and the working designs from the communications department, and spun out a number of ideas and possibilities.

They didn’t end up using any of the ideas, though. In a large organization, especially one that is connected to the federal government, there are a lot of stages of review to get through before something can make it to production. Still, there were a couple of ideas that I felt had some potential, and were worth developing further for the Unofficial SLAC Merchandise Store. One of these designs was the 10 Year Movie Poster.

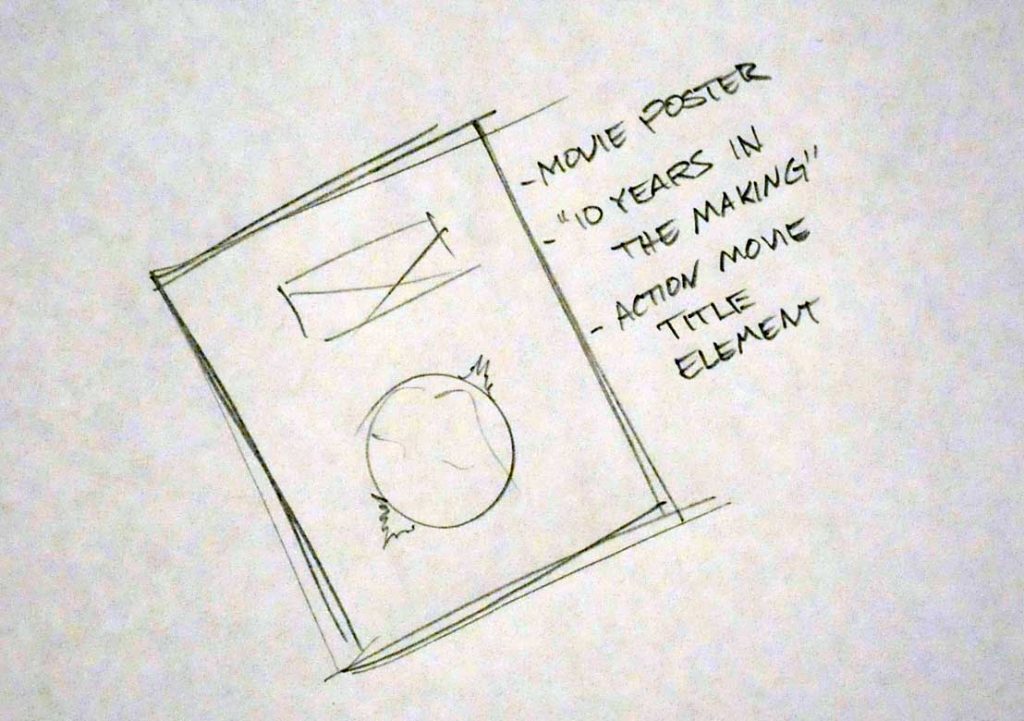

Concept

The concept was fairly simple. I wanted something that would call back to posters like that of the Transformers movies. My goal was to represent the planet from a perspective in space that would represent the world growing smaller, as physics pushes the limits of what we know. I decided that something simple was best, just the earth, some motion graphics style type. Given the concept was simple, I figured the production would be straightforward. However, I underestimated the difficulties involved.

Resolutions and Rendering

As part of the long range strategic planning campaign for the laboratory and university, I created a number of posters using analog techniques. This included a watercolor master measuring 18″ x 24″ and an acrylic original on canvas at 16″ x 20″. The watercolor in particular was a challenge because stretching watercolor paper that size ends up fairly difficult to do well. Moreover, when both of these were complete, reproduction still required high quality photos or large format scans. With that motivation, I decided to stay digital on the 10 Years poster.

I wanted the print size of the poster to be fairly large, at a high resolution. This meant producing final art at 10800 x 14400 pixels. 8k Ultra High Definition video comes in at 7680 x 4320, so this wasn’t that much larger, only about 3x. I’ve worked with data sets and images on this scale before, I figured load times would be tough, but my graphics machine could push the data around without issue.

I knew that I wanted something as photorealistic as I could get, and I knew I wanted something pulling from the motion graphics world of movie production. Therefore, I started out by using some of the resources from Video Copilot to build up an After Effects process for creating the planet with the appropriate lighting. This seemed promising until I attempted to render out the single frame I needed for the poster.

After Effects crashed. Hard. It did not like our planet. I tried sending the job through Media Encoder for fun: same result, different error messages. Now, I’m not an AE user by default. I started in computer graphics in Photoshop (version 1 or 2) and Maya (well, after cutting my teeth on Ray Dream Studio). Therefore, my reaction was one of “well, that’s what I get for trying a new tool”. I bounded over to Maya and built up my rig. Every render crashed at about 18 hours in.

At this point, I started to see a pattern. These codebases apparently weren’t meant to handle these large frames. I figured that they weren’t that much bigger than what effects houses would be working with for upcoming 8k and Imax features; as such, maybe I was just missing some configuration. Still, for giggles, I tried 3ds Max. When I got the same result I decided to reconsider my approach. That’s when I remembered an old piece of software I’d worked with in the past.

Terragen

I started using Planetside Software’s Terragen when it first came out. It was a 3d package for algorithmically generating terrain with atmospheric modeling and physics-based rendering. Future versions had unlocked the camera such that you could generate planetary scale terrain. Thing is, I hadn’t maintained my license since the last job I’d used it on, promotional material for the Nevada Lightning Laboratory, more than a decade back. For fun, though, I dug through old files to find the license key and an old installer, and tried running the program, which was successful. On a different OS, to boot.

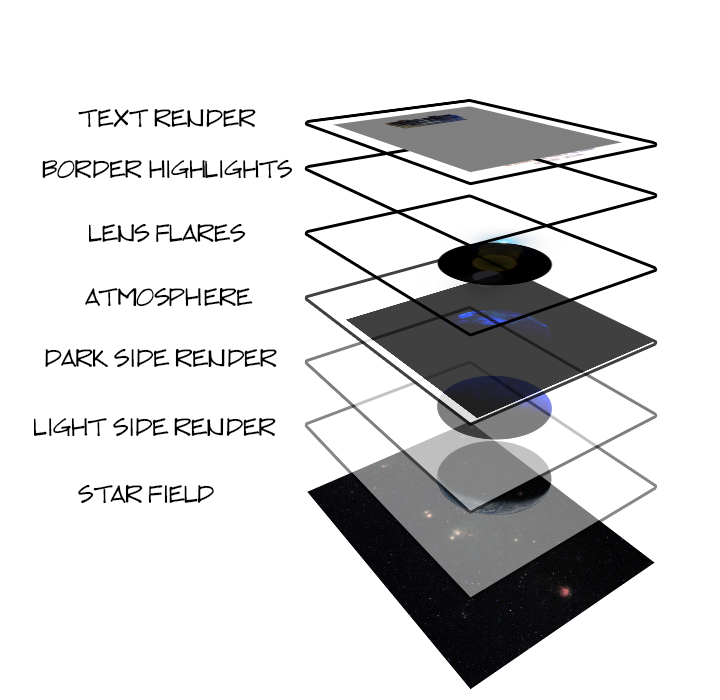

The process with Terragen goes a bit different than with a direct modeler. I was able to grab high res height fields from NASA’s and the USGS databases, and then use Terragen’s algorithms to modulate the height field data to generate additional higher resolution detail for our planet. I set up the system for the first pass of five that I would need, and set it loose. It took about 25 hours to complete, but it was successful. Old software, different OS, rendering a planet. Over the next week, I rigged and rendered the remaining passes, including nightside illumination, and cloud layers (generated with Terragen’s atmosphere tools).

Compilation and Text

Once I had the source graphics assets I needed, I began compiling the planet and star field for the bulk of the poster. This included additional Hubble data sets for realistic high res background material. All told, the Photoshop file ended up being beyond Photoshop’s image size limit, so I had to start decimating my data a bit. Still, the source file ended up being 1.6 GB.

Once I had the planet, I did the text model in Max and rendered out the result, comp’d it in and finished the poster.

Final Result

My take away from this is that even if you think you know the tools you are using, always be prepared to have to switch something out of your workflow. On the other hand, it helps to be clear on what you want to create before you start. I was creating a graphic featuring our planet. It would have made some sense to look at a planet renderer before trying other tools, especially one I’d used in the past.

All that aside, that’s effectively the longest single frame render I’ve had to run. The result is pretty fun, though, especially if you zoom in on the poster. Still, I don’t envy the effects houses when we start doing 14k HD video.